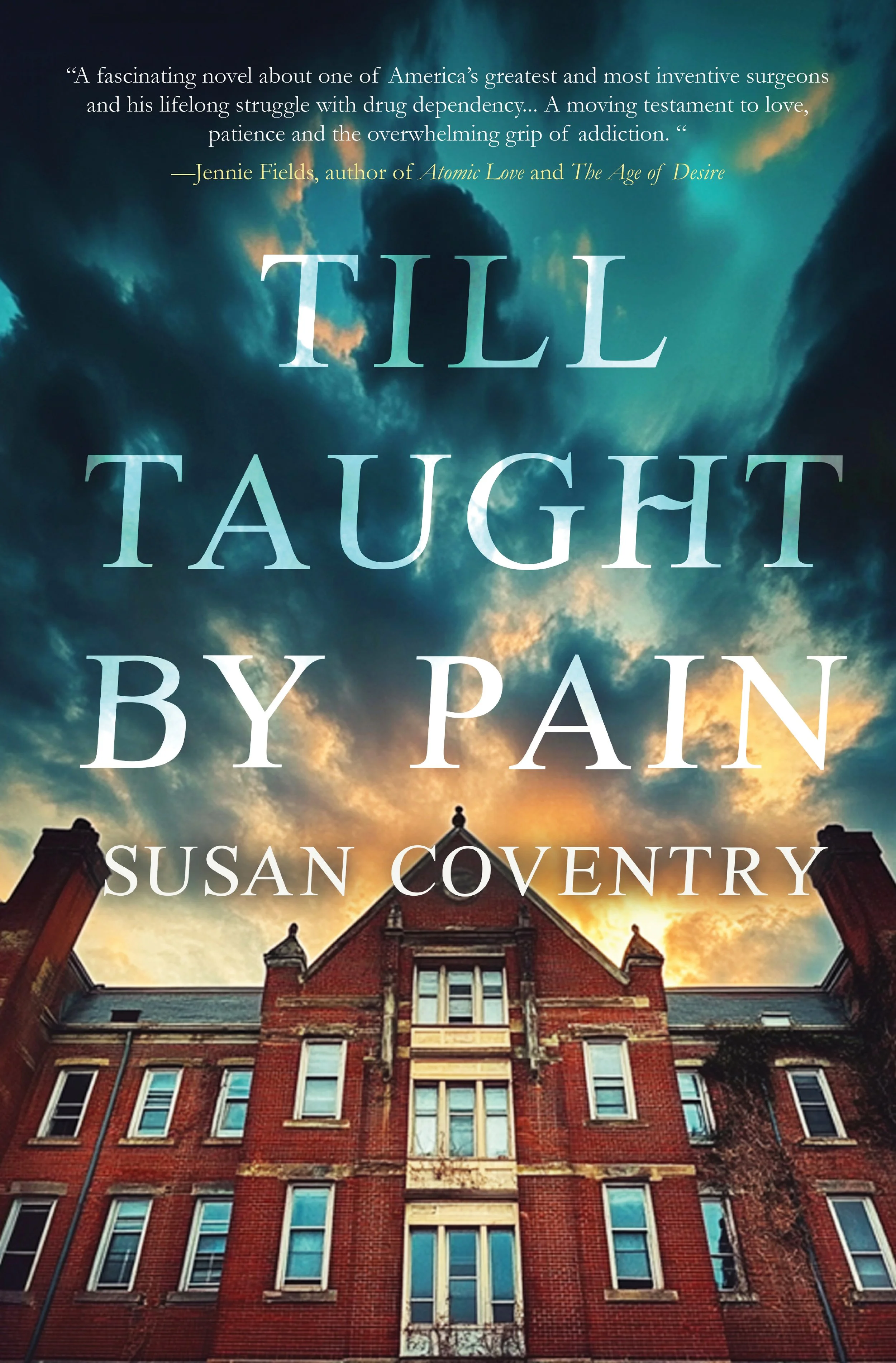

Spotlight: Till Taught by Pain by Susan Coventry

/Inspired by the groundbreaking discoveries of ether and chloroform anesthesia, William Stewart Halsted pursues a surgical career with relentless ambition, daring to perform operations deemed impossible by his peers. His reputation skyrockets with each bold success— until his quest for an effective local anesthetic leads him to inject himself with cocaine. Caroline, the niece of Confederate General Wade Hampton, seeks to escape the constraints of post-war South Carolina by training as a nurse. When she takes a position at the prestigious Johns Hopkins Hospital, she finds herself captivated by the brilliant yet troubled chief of surgery, Dr. Halsted. Till Taught by Pain is a poignant exploration of love and sacrifice, as Caroline grapples with the difficult choice between enabling her husband’ s addiction and supporting his pioneering career. As their lives intertwine, both must confront the consequences of ambition, the nature of love, and the toll of personal demons on their shared dreams.

Excerpt

Prologue

1922, October

Baltimore, Maryland

1201 Eutaw Place, Baltimore, MD

October 16, 1922

Dear Dr. Welch,

Thank you for your letter and for the trouble you have taken trying to satisfy Dr. Halsted’s sisters. As you say, the memories that I have are what stay with me and the hours between seven and half past eight when we would sit together are the most lonesome of the whole 24 hours…

—Caroline Hampton Halsted to Dr. W. H. Welch, October 1922

My vision blurred. Why was I doing this? No one had ever accused me of being a hysterical woman. I was never outwardly emotional; yet, here I was, tapping my private pain onto the keys of William’s typewriter to burden his most steadfast friend with my grief. Hadn’t Dr. Welch done enough for William over the years? Must he now also console the widow? An impossible task.

The letter would have to wait until I was more self-composed. I shouldn’t be dwelling on how empty the hours were when I had tasks to fill them. If William were here, he would give me one of those wry looks. I could see him doing it.

“Oh, William.”

Swiping the back of my hand over my eyes, I cleared away both tears and my late husband’s image and, instead, regarded his study. Off limits. It had always been off limits. I never bothered him here. This was where he lost himself in his work—that fiction we’d told one another, not with words but with the lack of them. The neat chaos supported the story: journals bearing snips of blue paper as markers, stacked into orderly piles; one basket of correspondence to answer and one for his secretary to file; a draft of the paper he’d been struggling with, more crossed out on the page than remained; scattered books. And downstairs in his library, there were case files, laboratory notes, and more shelves and shelves and shelves of books and journals.

I moved to the window to pull back the drapes. Drawing in a breath, I could still smell tobacco, a distinctly William smell. It was twined down into the antique furnishings, the drapes, and the oriental carpet, too deep to ever dissipate. How sad I could not relish it, but it stank.

It was quiet enough to hear the soft tick of his Gustav Becker wall clock, a gift from a German colleague. The beats sounded slow, as though minutes must now crawl by to rebalance time itself after the hours had slipped away from us so quickly.

Over the past year, William had determined more than once to sort through the accumulation of a busy, productive lifetime, but he was distracted from so desolate a task by the more urgent call to complete what he had started, to move on to more. He’d been so purposeful. All his life, he had been purposeful. That’s what people would remember. Wouldn’t they?

Perhaps not his sisters. Ridiculous creatures. With their Billy would want such-and-such and oh, we have to do this-and-that. Billy? In the end, I’d thrown up my hands. I was only a wife; I wasn’t about to argue with sisters. But neither would I trek up to New York to put him into a grave in the city he’d left all those years ago. I refused to see him buried un-der some hideously sentimental headstone with claptrap about angels. Thank God for Dr. Welch.

Dr. Halsted always said his sisters knew nothing about science and cared less.

Mrs. Halsted, with your permission, I’ll order the headstone.

He’d done it too:

William Stewart Halsted, M.D.

September 23, 1852-September 7, 1922

Professor of Surgery in the Johns Hopkins Hospital

Elegantly simple. William would have approved. And his sisters would not argue with the imposing Dr. Welch.

I would have to ask him what should be preserved for the university and the medical library. William’s friend Dr. Crowe said the books and journals were worth quite a bit and I should sell them. But William left me ridiculously well provided for. Surely, he expected me to give the books to the school.

More worrisome was what to do with all the accumulated paper.

Someone—one of William’s acolytes—would start nosing about, intent upon memorializing him. Would William prefer that only his published work survive to represent him? All this unfinished business, correspon-dence, notes for speeches—would it embarrass him to have people pawing through it? Would collected bits from William’s life—not only journal articles but private letters, personal recollections, half-remem-bered anecdotes—be pieced together like a jigsaw puzzle to summate the man he’d been? William would hate that. Ill-fitting pieces ruined a puzzle, and not all William’s pieces fit tidily.

He had to trust me to sift through the leavings, tidying them for pos-terity, before someone from the university arrived to cart all his precious papers away.

Precious papers—I had my own boxful back at High Hampton. My heart thudded painfully and heat rose to my face; William could write a pretty letter. I’d always intended to put a flame to them. One day. To keep them from a would-be biographer’s hands.

Lucy would have to do it. I couldn’t travel anywhere now. There was too much to do. Other things more damning to William’s dignity than love letters might still be locked away in drawers and cabinets. I had to be the one to find them.

William would want his secrets, his untidy pieces, buried with his ashes.

Excerpted from TILL TAUGHT BY PAIN by Susan Coventry © 2025 by Susan Coventry, used with permission by Regal House Publishing.

Buy on Amazon Kindle | Paperback | Bookshop.org

About the Author

Susan Coventry is a retired physician with a lifelong historical fiction obsession. Her first novel, The Queen’ s Daughter, was a YA historical set in the Middle Ages. She has since switched from YA to adult novels and moved on from medieval Europe to the turn-of- the-20th-century U.S. She lives in Louisville, KY with her historian husband, Brad Asher.

Connect: